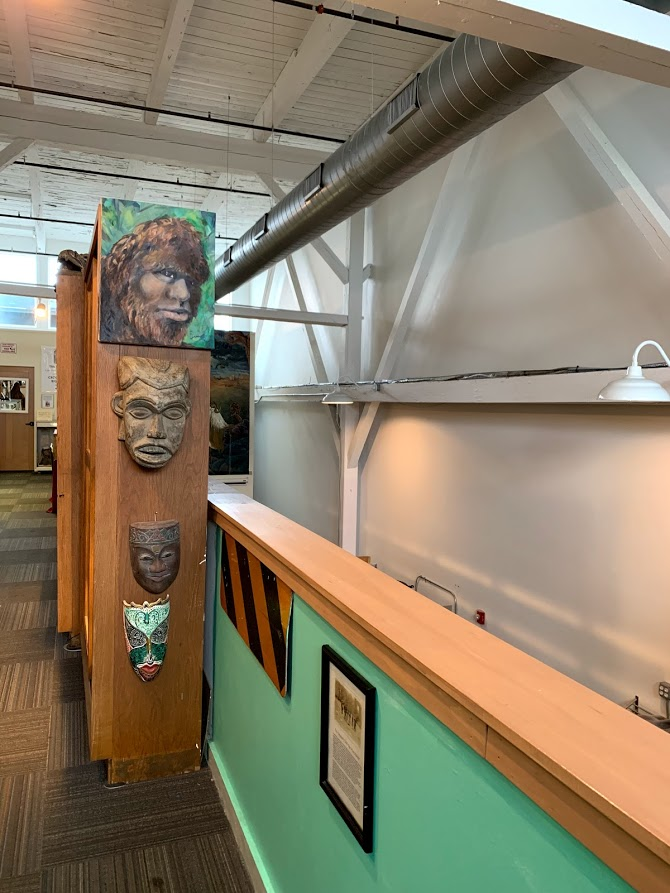

International Cryptozoology Museum, Portland ME, 2019

Photograph taken by Oliver

Loren Coleman’s portrait, masks, and models of bigfoot, etc as an unsorted, heterogeneous display

Contemporary Cryptozoology: Problematic Legacy Of Cabinet Of Curiosities

by Oliver

Bigfoot... AKA The Abominable Snowman, Sasquatch, Yeti…When we see the term “Bigfoot,” our minds bring us to the classic hoax photograph of a dark furry creature running away while looking back into the camera (1), as well as people wearing adventure gear and showing off footprint molds in a room full of objects mimicking a cabinet of curiosities (wunderkammer). That is also what you end up with if you internet search or visit a museum dedicated to cryptozoology.

Cryptozoology is part of fringe science or pseudoscience (2) along with ufology, numerology, transcendental meditation, electrogravitics, and more. These include different communities that often seem to be fun, harmless, and open-minded, but can be quite misogynistic, transphobic, homophobic, racist, and sexist. In this article I address the relationship between contemporary cryptozoology collections and the history of cabinets of curiosities.

Bigfoot Discovery Museum, Felton CA, 2016

Photograph taken by Fleur Williams

Displays of toys can demonstrate the collective human obsession of the search for bigfoot and capitalism

I want to acknowledge both skeptics’ and believers' devotion to challenging mainstream science, pushing boundaries and definitions, but also want to reimagine these fringe science investigations as inclusive and not dominated by fetishism and desire. My personal library is filled with books about unexplained phenomenons, UFOs, and critique of institutions—as a trans, queer, artist of color, I struggled with participating in most fringe science communities. We face the dominant culture of cis white men in these communities every day: Trans and gay people are often accused of being a secret government agenda for cutting population numbers; extraterrestrial beings transform into blonde white women with big breasts who are fetishised as the best sex a male abductee could have; tall white humanoids are seen as the wise extraterrestrial beings species; ancient civilizations’ accomplishments are merely alien technology, etc.

China Flat Museum Bigfoot Collection,Willow Creek CA,

Photograph from Atlas Obscura

Exhibit demonstrating how the adventures, the excitement of “hunting” [searching, seeking, and also actual hunting] cryptids and telling stories took over cryptozoology

Popularized by Bernard Heuvelmans (1916-2001), “cryptids” are defined as unknown species, supposedly extinct animals or hidden creatures like The Loch Ness Monster, Bigfoot, and more recently, pop-culture “monsters” like Mothman (3). They are what Sean Foley described as being “far from any resemblance to science” (4). Public collections of contemporary cryptozoology mostly start as personal collections and slowly transform into self-proclaimed museums without any museology background. Similarly, cabinets of curiosities (as museum precursors originating in the 16th Century) were collections of human exploration in arts and natural sciences. These personal collections, stored in princely homes, often demonstrated the owner’s knowledge by juxtaposing natural objects with man-made artifacts (5).

Expedition: Bigfoot The Sasquatch Museum,Blue Ridge GA, 2020

Photograph taken by Imgur user Albannaich819

With bigfoot as a frontispiece, hiking gears, and a logo with signifiers of half of an ethnographic mask and half of a bigfoot

In the collections of cryptozoology institutions, ethnographic objects like Native American masks are commonly collocated with models of cryptids, creating a sense of what Stephen Greenblatt defines as “wonder” but with an “unsorted, heterogeneous curation” (6). In the International Cryptozoology Museum (ICM), their curation is reminiscent of what Maura Reilly describes as “curatorial laziness” (7). Joe Nickell’s “Bigfoot As Big Myth: Seven Phases of Mythmaking” critiques believers’ need to use native masks and stories in the process of mythmaking (8). And Christine Davenne’s Cabinets of Wonder book directly points out the terminology “wunderkammer,” or “chamber of wonders” as evoking desire and myths (9).

International Cryptozoology Museum, Portland ME, 2019

Photograph taken by Oliver

Display mimicking cabinets of curiosities, filled with toys and souvenirs

Werner Muensterberger explained cabinets of curiosities’ popularization during human advancement in navigation and distribution of travel books: collectors were eager to demonstrate proof of other cultures and foreign goods. These collections ended up widely popular because of their entertaining nature and concoctions of factual data with quasi-utopian fantasies of the author (10). In like manner, the adventures, the excitement of hunting cryptids, and telling stories took over cryptozoology (11) and most collections demonstrate that, as is the case for the International Cryptozoology Museum, at which the upper floor is filled with the founder Loren Coleman’s personal items, including his computer, gear, and portraits of himself.

Expedition: Bigfoot The Sasquatch Museum,Blue Ridge GA, 2019

Video taken by Youtube user Quite Good and Awesome

Exhibit demonstrating how the adventures, the excitement of “hunting” [searching, seeking, and also actual hunting] cryptids and telling stories took over cryptozoology

Thom Powell’s opening in his lecture “Searching for Sasquatch: Cryptozoology and the Science & Folklore of Hidden Animals” also accuses that “Bigfoot” is a contemptible name (12). Fetishising a specific body part of a whole species, (or multiple species) is not the only problem in cryptozoology. Cabinets of curiosities also once used crocodile as their token of “fascination” and “exoticism,” as it was “undocumented” in the West and these originated from Africa, where according to François Rabelais in 1564 was “a place that produced new and monstrous things” (13). While the International Council of Museums (ICOM) and countless museums are overcoming their historical misrepresentation and cultural appropriation, the curation of collections in cryptozoology museums seems to fail as they latch onto ethnographic objects even though any relationship with Bigfoot or other cryptids is still yet to be understood (14).

North American Bigfoot Center, Boring OR, 2019

Photograph taken by Wesley Lapointe

Ethnographic objects juxtaposed with bigfoot related objects

Historically, cabinets of curiosities were not only filled with “foreign goods,” taxidermic animals, and skeletons as proof that “other cultures” and “worlds” exist, but also objects fabricated as results of human ingenuity and imagination (15). Contemporary cryptozoology displays often include toys, souvenirs, decorations, fan-art etc. While the displays of toys and pop culture demonstrate the collective human obsession with the commodified search for cryptids, it’s also made up of a problematic analysis like in the cabinets of curiosities. The whole museum is read as one cabinet of curiosities, filled with objects that do not necessarily relate to cryptozoology, and audiences were suddenly offered to join the cult of self-indulgence. Toys, fan-art, ethnographic objects, ambiguous footprints, etc. are meshed together to seem as “scientific evidence” and turn out irresponsible, careless, at many times racist, and certainly moving away from what Heuvelmans envisioned cryptozoology to be—studying legends and myths, protecting the “hidden animal,” and when the animal is finally scientifically recognized, return its research to zoology (16).

International Cryptozoology Museum, Portland ME, 2019

Photograph taken by Oliver

A bigfoot painting juxtaposed with ethnographic objects without descriptions

Cabinets of curiosities have a problematic history of fetishism (17) and are extremely biased since they only display the perspective of their arrangers (18). These tendencies are seen in contemporary cryptozoology and institutional collections. After 50 years of his investigation, Zhou Guoxing concludes whether Bigfoot exists or not, visualizing the human psychological need for mysteries in this field of study (19). Contemporary cryptozoology seems to continue the legacy of cabinets of curiosities, representing human desire (prone to voyeurism and hunting) as showing off our “treasures” to others (20).

International Cryptozoology Museum, Portland ME, 2019

Photograph taken by Oliver

Display case showcasing objects with no description

As a field of study, cryptozoology is shutting down a lot of folks interested in introducing discourse with analyses of language, anthropology, visual arts, zoology—including queer and people of color. When a discipline gives in to the human desire to capture and show-off, and it creates barriers by being commercialized, fetishized, and dominated by the Western lens, its exclusion from academia only remains to be seen due to its self-indulgence.

Oliver, a research-based artist, dwells in themes like archiving, cataloguing, tautology, and pessimism to explore ways to declare existence. They see museums as vehicles of truths, and these truths are unstable. Interested in fringe science, they aim to explore alternative ways to write about ufology and to create an inclusive space within the fringe science communities for queer art-workers.

Instagram: @the___museum

Website: www.999oliver666.com & www.themuseumm.com

Footnotes:

Kal K Korff and Michaela Kocis, “Exposing Roger Patterson’s 1967 Bigfoot Film Hoax,” Skeptical Inquirer28, no. 4 (2004), https://skepticalinquirer.org/2004/07/exposing-roger-pattersons-1967-bigfoot-film-hoax/)

Lorenzo Rossi, “A Review of Cryptozoology: Towards a Scientific Approach to the Study of ‘Hidden Animals,’” in Problematic Wildlife: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach, ed. Francesco Maria Angelici (Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2016), pp. 573-588), 575.

Rossi, 575,577.

Mark Bessire and Sean Foley, “Cryptozoology As Art,” in Cryptozoology: Out of Time Place Scale (Lewiston, Maine: Bates College Museum of Art, 2006), pp. 74-79), 74,75.

Christine Davenne et al., Cabinets of Wonder (New York, NY: Abrams, 2012), p.13), Florence Fearrington, “Introduction,” in Rooms of Wonder: From Wunderkammer to Museum 1599-1899 (New York: The Grolier Club, 2012), pp. 9-16), 9,11

Stephen Greenblatt, “Resonance and Wonder,” in Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, ed. Ivan Karp (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press , 1991), pp. 42-56)

“…...the touchy subject of curatorial laziness, an unwillingness to think beyond the precedents, out of the box, around the block out of the comfort zone that can result in involuntary misogyny, racism, homo/lesbophobia.” Maura Reilly and Lucy R. Lippard. “The More Things Change...” In Curatorial Activism: Towards an Ethics of Curating, (London: Thames & Hudson, 2018),10.

Joe Nickell, “Bigfoot As Big Myth: Seven Phases Of Mythmaking,” Skeptical Inquirer 41, no. 5 (2017), https://skepticalinquirer.org/2017/09/bigfoot-as-big-myth-seven-phases-of-mythmaking/)

Davenne, 13.

Werner Muensterberger , “The Age of Curiosity,” in Collecting: An Unruly Passion. Psychological Perspectives (Princeton University Press, 1994), pp. 183-203), 184,187.

Sharon Hill, “Cryptozoology And Pseudoscience,” Skeptical Inquirer 21, no. 3 (May 2012), https://skepticalinquirer.org/newsletter/cryptozoology-and-pseudoscience/)

Thom Powell, “Searching for Sasquatch: Cryptozoology and the Science & Folklore of Hidden Animals.” (Lecture, University of Oregon, Eugene, 2012)

Rabelais, Pantagruel in the Fifth Book, (1564), quoted in Christine Davenne et al., “Exoticae: Monsters from Elsewhere” in Cabinets of Wonder (New York, NY: Abrams, 2012): 129

Nickell, 2017., Powell, 2012.

Muensterberger, 17.

Bernard Heuvelmans, “Histoire de la Cryptozoologie—Seconde partie essor et Officialisation de la Cryptozoologie.,” Criptozoologia 3 (1997): pp. 23-40), quoted in Lorenzo Rossi, “A Review of Cryptozoology: Towards a Scientific Approach to the Study of ‘Hidden Animals,’” in Problematic Wildlife: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach, ed. Francesco Maria Angelici (Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2016), pp. 573-588.

Mark Bessire, and Raechell Smith. “Introduction.” In Cryptozoology: Out of Time Place Scale, (Lewiston, Maine: Bates College Museum of Art, 2006), 11.

Sarah Rose Sharp, “Curating a Contemporary Cabinet of Curiosities.” Hyperallergic, March 5, 2015. https://hyperallergic.com/188131/curating-a-contemporary-cabinet-of-curiosities/.

Zhou Guoxing, “Fifty Years of Tracking the Chinese Wildman,” The Relict Hominoid Inquiry 1:118-141, 2012, https://isu.edu/media/libraries/rhi/research-papers/Zhou__Tracking-the-Chinese-Wildman.pdf)

Monica Khemsurov, “Sight Unseen,” Sight Unseen, 2012, https://www.sightunseen.com/2012/10/cabinets-of-wonder/)

Bibliography

Bessire, Mark. Cryptozoology: out of Time Place Scale. Lewiston, Maine: Bates College Museum of Art, 2006.

Bessire, Mark, and Sean Foley. “Cryptozoology As Art.” In Cryptozoology: Out of Time Place Scale, 74–79. Lewiston, Maine: Bates College Museum of Art, 2006.

Davenne, Christine, Christine Fleurent, Charlotte Blum, Méry Véronique, and Nicholas Elliott. Cabinets of Wonder. New York, NY: Abrams, 2012.

Davenne, Christine. “Exoticae: Monsters from Elsewhere” in Cabinets of Wonder. 124-159. New York, NY: Abrams, 2012.

Fearrington, Florence. “Introduction.” In Rooms of Wonder: From Wunderkammer to Museum 1599-1899, 9–16. New York: The Grolier Club, 2012.

Feder, Kenneth L. Frauds, Myths, And Mysteries: Science and Pseudoscience in Archaeology. 1st ed. Mountain View , California: Mayfield Publishing Company, 1990.

Greenblatt, Stephen. “Resonance and Wonder.” In Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display, edited by Ivan Karp, 42–56. Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press , 1991.

Heuvelmans, Bernard. “Histoire De La Cryptozoologie—Seconde partie essor et officialisation de la Cryptozoologie.” Criptozoologia 3 (1997): 23–40. Quoted in Rossi, Lorenzo. “A Review of Cryptozoology: Towards a Scientific Approach to the Study of ‘Hidden Animals.’” In Problematic Wildlife: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach, edited by Francesco Maria Angelici, 573–88. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2016.

Hill, Sharon. “Cryptozoology And Pseudoscience.” Skeptical Inquirer 21, no. 3 (May 2012). https://skepticalinquirer.org/newsletter/cryptozoology-and-pseudoscience/.

Khemsurov, Monica. “Sight Unseen.” Sight Unseen, 2012. https://www.sightunseen.com/2012/10/cabinets-of-wonder/.

Muensterberger , Werner. “The Age of Curiosity.” In Collecting: An Unruly Passion. Psychological Perspectives, 183–203. Princeton University Press, 1994.

Nickell, Joe. “Bigfoot As Big Myth: Seven Phases Of Mythmaking.” Skeptical Inquirer 41, no. 5 (2017). https://skepticalinquirer.org/2017/09/bigfoot-as-big-myth-seven-phases-of-mythmaking/.

Powell, Thom. “Searching for Sasquatch: Cryptozoology and the Science & Folklore of Hidden Animals.” Lecture, University of Oregon, Eugene, 2012.

Korff, Kal K, and Michaela Kocis. “Exposing Roger Patterson’s 1967 Bigfoot Film Hoax.” Skeptical Inquirer 28, no. 4 (2004). https://skepticalinquirer.org/2004/07/exposing-roger-pattersons-1967-bigfoot-film-hoax/.

Rabelais, Pantagruel in the Fifth Book, 1564. Quoted in Christine Davenne et al., “Exoticae: Monsters from Elsewhere” in Cabinets of Wonder (New York, NY: Abrams, 2012): 124-159

Reilly, Maura and Lucy R. Lippard. “The More Things Change...” In Curatorial Activism: Towards an Ethics of Curating, London: Thames & Hudson, 2018.

Rossi, Lorenzo. “A Review of Cryptozoology: Towards a Scientific Approach to the Study of ‘Hidden Animals.’” In Problematic Wildlife: A Cross-Disciplinary Approach, edited by Francesco Maria Angelici, 573–88. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2016.

Sharp, Sarah Rose “Curating a Contemporary Cabinet of Curiosities.” Hyperallergic, March 5, 2015. https://hyperallergic.com/188131/curating-a-contemporary-cabinet-of-curiosities/.

Zhou, Guoxing. “Fifty Years of Tracking the Chinese Wildman.” The Relict Hominoid Inquiry 1:118-141, 2012. https://isu.edu/media/libraries/rhi/research-papers/Zhou__Tracking-the-Chinese-Wildman.pdf.

![China Flat Museum Bigfoot Collection,Willow Creek CA, Photograph from Atlas ObscuraExhibit demonstrating how the adventures, the excitement of “hunting” [searching, seeking, and also actual hunting] cryptids and telling stories took over cryptozoolo…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d23fc4db9f14e0001763c43/1593823272918-JKPEGNZSPEV5ILXM9E11/pasted+image+0+%286%29.png)

![Expedition: Bigfoot The Sasquatch Museum,Blue Ridge GA, 2019 Video taken by Youtube user Quite Good and AwesomeExhibit demonstrating how the adventures, the excitement of “hunting” [searching, seeking, and also actual hunting] cryptids and telling s…](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5d23fc4db9f14e0001763c43/1593823499120-9QTFWNGA36R4OHSH5C7T/Screenshot+2020-05-03+at+9.44.06+PM.png)